The Internet’s steep fall from its earliest promise is tragic. Here’s what it will take to get it back to the way it was supposed to be.

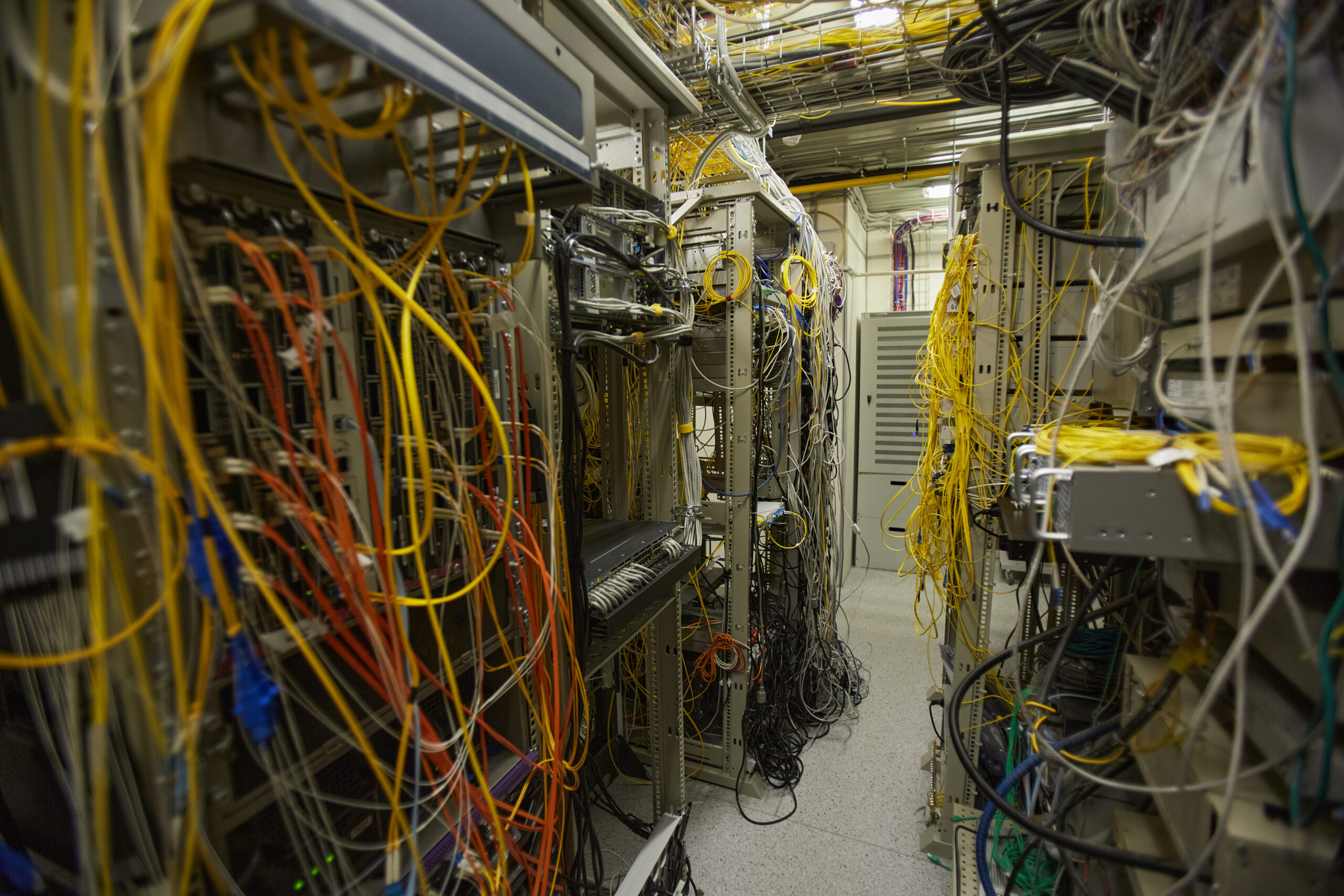

Few people can actually say, “I was in the room” when the Internet happened. I can say this because I had an up-close view of the Internet’s earliest days (circa 1994 – 2000) due to the fact that I was working at Lucent Technologies (hardware side) and Bell Labs (software side). Myself, along with my colleagues who were working on this great experiment, were highly aware that we were witnessing the birth of an entirely new concept. We sensed that the Internet was possibly one of the most remarkable transformations in human history. It became a sacred mission, treated with great care as we were cognizant that the decisions, the technologies, and protocols we were developing would be far-reaching.

Uniquely, between Lucent Technologies hardware and Bell Labs software, we developed a conceptual and practical understanding of how the Internet could and should work. This created the space for us to speculate about digital privacy, monetization, search, and eCommerce as Internet was still being incubated in the tech womb. In those early Internet days, let’s recall:

- Google was just getting started and faced heavy competition from other browsers.

- Amazon was just an online bookseller and losing money to boot.

- Zuckerberg was about ten years old – not even a Bar Mitzvah boy yet.

- Steve Jobs had just returned to Apple after a 10-year exile.

- There was no WordPress or SSLs, or eCommerce platforms.

- And most definitely, there were no cookies or tracking digital audiences or smart devices like Siri and her cousin, Alexa.

As we learned to find our sea legs on this rolling Internet ship, we got some things very right, especially in understanding the profound impacts of information sharing and broad connectivity. We understood what tech would be needed to go from Dial-up to DSP to broadband with “smart” devices. We saw how tech, like drag and drop website development that could power eCommerce, communications, and collaboration, was game-changing for small businesses. And all of us could imagine how, with easy access to trusted information, the Internet could improve the lives of millions – even billions of people.

Other things we got very, very wrong. While Bell Labs developed privacy protection in a product called The Anonymizer, it never came to market because it didn’t seem necessary to protect browsing behaviors. Nor did we predict that the killer monetization application of the Internet, advertising, would create a toxic system that hurts everyone. We could see that going to a library to search for information or that “banker’s hours” were becoming anachronisms, losing all meaning, but we missed entirely the security opportunities of visual search engines.

Internet’s fall was fast and furious.

The Internet’s inextricable decline may not have been noticed by most, but it was particularly painful for me to bear witness to its almost complete degradation 15 years later.

When I juxtapose the Internet that could have been to what the Internet became, I can trace the decline to two overlapping yet destructive commercial ecosystems; a. The Surveillance Economy and; b. The Misinformation/ Shock Content Economy.

These two economies synergistically devolved the Internet from its promise to improve people’s lives to a low of “productizing” people’s identity and monetizing their emotions.

Here’s how.

a. The Surveillance Economy wreaks real damage across the digital landscape by productizing “Judy Consumer:”

Commercial interests ignored Internet’s DNA as a content-serving engine instead favoring the easier to game “people tracking” business model. These data firms engaged in questionable user data harvesting practices despite people’s preference to maintain their privacy.

All this data harvesting of user information can be, plausibly, be described as the biggest data heist of all time.

These data assets were relatively cheap to procure since they eliminated all nasty data fees or user permission protocols, clearing the way for data firms to sell and resell this low cost data at VERY high prices. This created a lot of hugely profitable businesses while “Judy Consumer” lost her digital soul.

b. The Misinformation/ Shock Content Economy monetizes outrage content, spawning the modern, digital version of yellow journalism.

The monetization model of misinformation and shock content is to exploit our emotions with outrage thus increasing engagement and ad revenue proportionately. It is such a profitable business model because the whole system relies on cheap content development costs (no human fact checkers needed) and an obscure ad supply chain that allowed bad actors who pump out this disreputable content to generate revenue via ad buys. (I go into great detail about how the Misinformation/ Shock Content Economy works here.). It’s not that advertisers overtly wanted to run on these sites, but the murky supply chain of digital media meant that very very often, advertisers had no idea where their ads ran.

Taken together, The Surveillance Economy and The Misinformation/ Shock Content Economy obliterated any semblance of what the Internet should have been. These pillars of the Internet’s monetization structure worked well for individual adtech firms (The Trade Desk CEO reported got a comp package of over $800 Million according to WSJ) but had a catastrophic impact on people because all we are left with are trust gaps where; “…conspiracy theories become true, and villains become heroes. It’s where pizza joints can become sex trafficking centers, and George Soros somehow is a master puppeteer pulling the strings on world events.” (Read more here – The Unknowable Distortion Field is eating the world.)

It doesn’t have to be this way. The way to move forward is by looking back at the earliest days of the Internet and taking inspiration from there.

The future of the Internet lies in rediscovering how the Internet was supposed to be – The Trust Web.

We can’t have a vision of the future if our perspective is confined to the Internet of the last 15 years. The challenge is that tech innovators tend to have a digital-centric view of the world, lacking any other perspective that can create viable alternatives. Too often, all we see are ever convoluted versions of current methods of online experiences.

If we suspend what we know about the Internet and remember what we knew about Internet’s mission and purpose, we can ideate concrete “mid-course” corrections to get the Internet back on track.

I believe the Internet’s path back to the beginning rest on three pillars.

1. Give control back to people

It’s important to remember that the analog world was people-controlled. People decided what books to explore at the book store and what music they played on their Walkman.

Today, individuals’ digital experiences are completely subject to the whims of AI and the tech rules of a particular site.

- There is no standard around how to opt-in or out of privacy settings from site to site, baffling the most scrupulous visitor.

- Artificial Intelligence drives what organic search results you see, what music you hear, and who you connect with on social media. The human element is just background noise.

- Algorithms tag and bag digital profiles with efficiency, but the data is detached from the real person behind the profile. This information is gathered relentlessly and sold and resold in an auction platform with an eerie echo of a very distant past.

- The serendipity of unexpected discovery journey ala Stumble Upon from 2002 has been replaced with AI’s muscly and irrepressible need to categorize individuals into static groups. If, for instance, you explored a conservative political podcast in the past, going forward you will be shown a lot more conservative content whether you want it or not. Topic data preferences are attached to individuals without the context to understand whether those interests are short-lived or one-offs and not really core to a person’s digital profile.

Tech has become people’s Internet experiential arbiter, and that is becoming unsustainable. As the Internet enters middle age, the scale of its operations means more data mischaracterizations, more AI misfires and more mega algo misses.

All these glitches compound over time, making the Internet less useful, less efficient, and less trusted. Search results wander further from what you really want to know or we have to endure overwhelming content tsunamis with negative and untrusted content that manipulates our emotions.

A trusted Internet will be an Internet people create for themselves – not an Internet created via large corporate intermediaries.

2. Reimagine adtech in the context of a true content-centric tech stack.

As someone who was “in the room when it happened,” the monetization of the Internet was conceptualized to be content-centric but ended up looking very different.

In fact, adtech perverted the original vision for the Internet by tossing aside content’s productive role in creating trusted interaction between people, organizations, publishers, and institutions in favor of tracking people – an ethically challenged path that does nothing to build trust bridges between the different stakeholder groups.

Amidst the experiential trust wreckage, The Surveillance Economy emerged as an easy, highly profitable business. This then attracted a wide array of players and technologies that were hard to organize, harder to vet, and even harder to trust.

The very beating heart of the Surveillance financial model was its murky “people tracking” data intertwined with an even murkier ad supply chain.

For years, this system was vigorously defended by people who were perfectly happy with the way things were because they knew they had a good thing going. They didn’t have any appetite to do better or to conceptualize alternatives despite the reality that targeting “profiles” is not as productive as using topics to attract topic-intent audiences. (This article describes how passionately adtech folks will defend their flawed system; Reddit radicalized me.)

Tim Cooke said it best when he explained that people tracking is not necessary for digital advertising to work. “Advertising does not need vast troves of personal data to succeed. We’re here today because the path of least resistance is rarely the path of wisdom. Too many are still asking the question ‘How much can we get away with?’ – when they need to be asking,’ What are the consequences?” (Source: Inc – January 2021)

The key to restoring the Internet, therefore, is by embracing – not fighting – the content-serving DNA of the Internet through a contextual targeting monetization model.

And just like that contextual is in. Yes, yes – I know everyone is jumping on the contextual bandwagon, but no one is really serious about it as a fully functional architecture.

There’s been no innovation in today’s contextual targeting infrastructure. The contextual targeting tools and networks we have are lame; keywords can misfire a lot, interest classifications are too broad and many “native” platforms (a.k.a – contextual networks) are so low quality they have become fodder for the comedy circuit. There are no analytics breakthroughs that allow advertisers to track which topics perform well instead, instead clinging desperately to determine “who” converted despite the obvious niggling issue that tracking the “who” probably means violating the “who’s” privacy.

For real contextual targeting to work right, it need a real adtech stack that is holistic. There needs to be a real topic data layer (most definitely not keywords), new buying systems that take the scale out of digital buys and replace them with platforms that can put ads next to relevant content. And it all comes together with a different approach to attribution that leaves behind tracking “who” converted in favor of what topics drive conversions.

By aligning digital marketing tech around Internet’s content-centric DNA, we go forward by going back to Internet’s DNA as a content serving engine.

3. Nextgen social networks ride on a decentralized Internet.

It’s easy to mock Musk for wanting to buy Twitter or to diss Zuckerberg for his desire to remake the Internet in his own image with Meta. Still, both reflect a profound realization that we need a do-over in much of the Internet and social media.

Early on, social media’s “network effect” seemed unassailable; scale the network because the bigger a social network got, the more it was insulated from disruption and competitors. This concept was initially true, especially during these formative years of 2010 – 2015. Since then, study after study has demonstrated the vulnerabilities of such large networks which is why the Internet and social media are rife with bullying, misinformation, and pervasive issues with trolls and bots.

Common sense wants a do-over, but common sense also understands that a do-over cannot be executed by the same folks who live in the mindset of “mega” everything – from Musk to Zuckerberg. All they can do is reinvent variations of their current business models.

This is precisely why these business leaders are highly vulnerable to being disrupted by new work both at the fringes and at the core of the Internet. The fringe players are focused on blockchain ID management, decoupling data from apps, or AI-driven individual data management so that, for instance, you can give some of your Amazon data to Walmart to see if Walmart can beat the prices for stuff you bought.

Working at the core of the Internet, there’s furious activity around Web 3.0 in many dimensions, from decentralized networking and user data management to blockchain-powered trust protocols and AI powered contextual adtech stacks. (Sidebar: Let’s fully appreciate the supreme irony that as we look to make the Web more human – we name this effort using software versioning conventions.)

Irrespective of fringe or the core initiatives, these efforts will result in a revolutionary power shift from large corporations to tech that goes to the consumer edge for individual user control.

Go forward by looking back to the beginning.

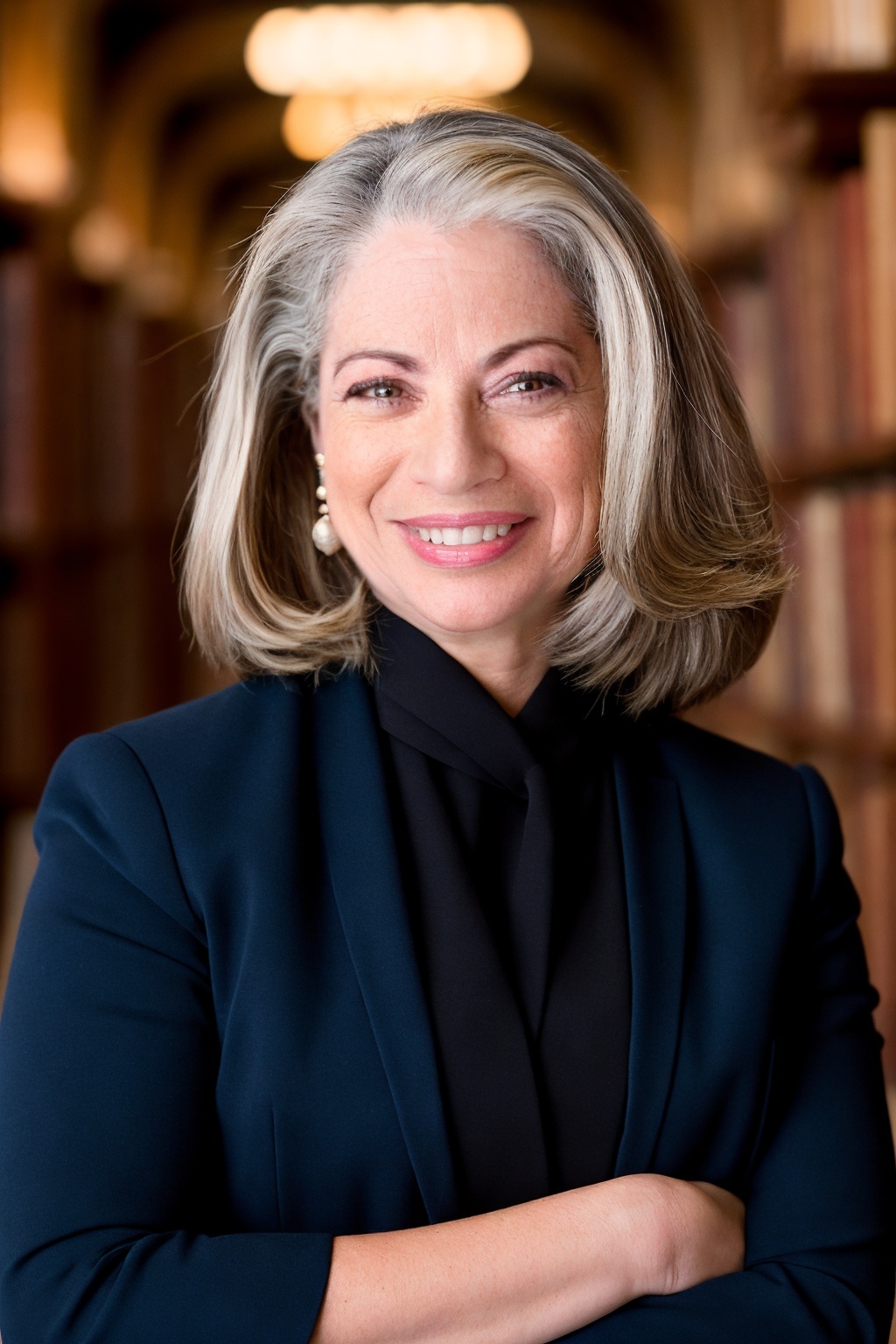

The cognitive disconnect between what the Internet should have been and what it is today is keenly felt by those of us who were in the room when it happened.

In 2009, 10 years into the Internet’s development, I bought the URL, The Trust Web, because it seemed to me that the trust aspect of the Internet was underdeveloped. Today, that still remains largely true. Yet many of us are taking the concept of The Trust Web and building it to allow the Internet to function as it was meant to be; empowering people to optimize their relationships between advertisers, publishers, and each other so that the Internet experience is based on trust.

Imagining the Internet as it was supposed to be is hard for most, but not for me. My clarity of vision is to refashion the Internet into what the Internet was supposed all along. My work takes on an urgent purpose because, after all, there aren’t many people left who were; “in the room when it happened.” That long view is necessary to get the Internet we were supposed to have all along.